The Constitutional Court Art Collection

Part of what makes the Constitutional Court such a remarkable building is its fusion of architecture, art and adornment. It is a space that reflects a profound interest in humanity and a deep yearning for justice, both of which are evidenced in the court’s aesthetic, including its permanent, curated art collection.

The curation of this collection was driven by Justices Albie Sachs and Yvonne Mokgoro, who began the process of decorating the court with a budget of just R10 000. This sum was spent outright when Sachs and Mokgoro commissioned Joseph Ndlovu to create a tapestry that would reflect humanity and social interdependence in the new democratic South Africa’s Bill of Rights. The tapestry, titled Humanity, is on display in the collection today.

A spark, however, had been ignited, and in a spontaneous, serendipitous upswell of interest, artists quickly came forward to be a part of the new Constitutional Court (even though the court at Constitution Hill was still under construction at the time).

Prominent South African artist Cecil Skotnes donated a panel depicting his interpretation of democracy, a work called Freedom. Willie Bester’s Discussion, William Kentridge’s Sleeper – Black, Robert Hodgins’ Hotel with Landscape and Marlene Dumas’s The Benefit of the Doubt soon followed. A special ceremony was held for the installation of The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent by Judith Mason, a work that is based on proceedings at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and one that is now perhaps the court’s most famous piece.

The court’s walls – first at its humble premises in Johannesburg and later at Constitution Hill – quickly began to fill up, and ultimately spilled over into the judges’ chambers and meeting rooms.

Of course, additional funding was required to curate the collection. With the new government focused on health, education and other key areas, and investment from the private sector prohibited because the court cannot accept support from private firms or individuals who could one day be litigants before it, the court accepted grants from various European governments and from North American philanthropic organisations.

Today, art not only adorns the walls of the Constitutional Court at Constitution Hill. It is in the foyer’s chandeliers and light fittings, designed by sculptor Walter Oltmann. It is in the court’s rugs, carpets and acoustic panels, designed by Andrew Verster. It is in the engraved doors, carved gates and mosaicked columns, and in the abundant use of texture and symbolism.

More information is available on the Constitutional Court Art Collection website.

Signature pieces

The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent

Artist: Judith Mason

Year: 1998

Medium: Mixed medium, oil on canvas

Also known as the Blue Dress, this is considered the signature piece of the collection. Inspired by two executions by apartheid security police, the piece aims to give a voice to those whose voices were stripped away from them. Using mixed media and oil on canvas, Mason’s artwork tells the stories of Phila Ndwandwe and Harald Sefola, whose deaths were voiced by their respective killers at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Ndwandwe was imprisoned, tortured and kept naked for 10 days by police in an attempt to find information before she was fatally shot. When her body was exhumed by the TRC, the underwear she made for herself out of a thin blue plastic bag was found still wrapped around her pelvis. Sefola was electrocuted by security forces in a field outside Witbank. Waiting to die, he requested to sing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, which is now the national anthem of South Africa.

In creating the accompanying piece, Mason collected discarded blue plastics bags and sewed them into the iconic dress depicted in the piece. The dress can be viewed alongside the painting. Justice Albie Sachs, a primary player in building the Constitutional Court collection, considers the piece “one of the great pieces of art in the world of the late 20th century, that emerged out of our artistic imagination, our social experience, our sensibility”.

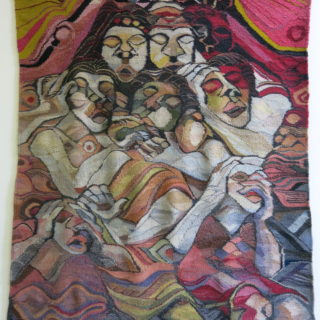

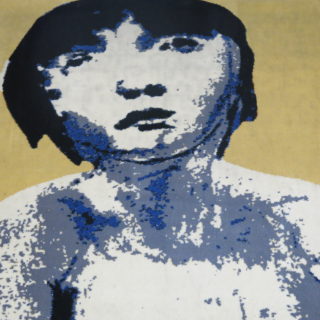

Humanity

Artist: Joseph Ndlovu

Year: 1994

Medium: Fibre

Commissioned by the Constitutional Court’s first justices, Justices Albie Sachs and Mokgoro, the aim of the piece was to decorate the courtroom in a manner that would befit the dignity of everyone entering the court seeking justice.

Ndlovu’s tapestry features a series of figures with closed eyes, embracing in a serene manner against warm and vibrant colours. The tapestry is perhaps the most important piece in the collection, expressing principles of justice and reconciliation. The court’s entire decor budget of a mere R10 000 was used for Ndlovu’s commissioned work. Today the collection is valued at more than US$5-million through donated works by more than 400 artists.

History

Artist: Dumile Feni

Year: 2003

Medium: Bronze

Dumile Feni spent more than two decades in exile in New York. However, just as he was about to return to South Africa in 1991, he passed away. Initially a small clay artwork made by Feni in 1987, the Tallix Art Foundry in Brooklyn, New York, enlarged and cast the work in bronze in 2003. Today the large sculpture stands proudly at the entrance to the Constitutional Court.

Depicting a master-slave relationship and its brutal nature, a large yoked figure draws a cart where two much smaller figures sit on top of another human figure. The title of the work, History, draws on the brutal treatment of black labour to build a colonial empire that evolved into the brutal treatment of black bodies under apartheid.

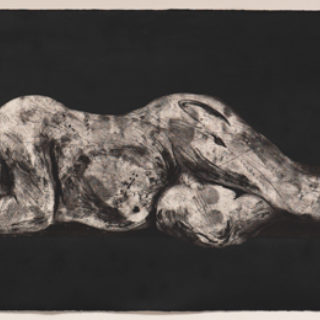

Sleeper – Black

Artist: William Kentridge

Year: 1997

Medium: Charcoal

Sleeper – Black is one of the etchings produced as part of the film project Ubu Tells the Truth (1997), originally created to form part of the multimedia theatre work, Ubu and the Truth Commission (1997). One of the fundamental themes in Kentridge’s films follows the desire to remain oblivious to reality and history. Characters are often locked in a constant state of denial, specifically over the exploitation and abuse of African people spanning from colonialism to apartheid.

The work is deeply metaphoric, where sleeping in all of Kentridge’s works suggests blissful ignorance. All sleeping characters always wake up, however, resulting in a painful self-knowledge connecting the character to their own history and humanity. Sleeper – Black is one in a series of Sleeper etches portraying the experience of waking up to reality.

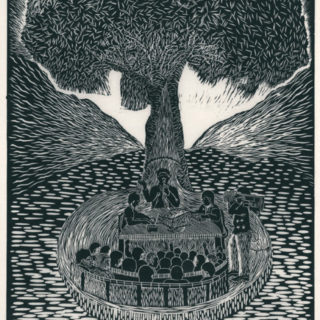

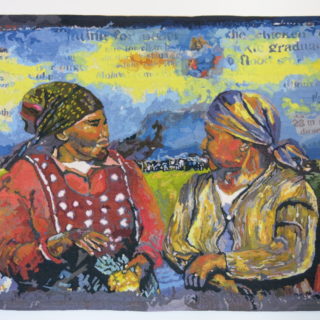

Making Democracy Work

Artist: Sandile Goje

Year: 1996

Medium: Linocut on paper

Goje’s linocut depicts a contemporary society embodying democracy, transparency and community by having court proceedings happen under a tree. The Constitutional Court adopted the “justice under a tree” metaphor as one of its core fundamentals, as the ceremony under the tree represents transparency and protection, and draws on the tradition of trees being community meeting places. Goje’s linocut is thus emblematic of the Constitutional Court, suggesting a unique and open South African solution to law in a post-apartheid environment.

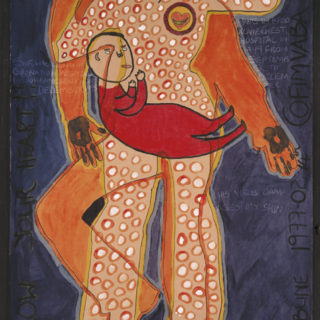

Body Maps

Artist: Ncedeka Mbune

Year: 2009

Medium: Digital print on paper

Body Maps is a limited-edition series of self-portraits created by 12 HIV-positive women from the Bambanani Women’s Group in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. The portraits feature an intensely intimate view of the artists, mapping out their life stories that led them to that particular moment. The maps are accompanied by essays explaining the imagery behind the maps.

Mbune’s map begins, “When I see this picture I feel much happier just because when I look at it, I see what I can’t see when I look at myself in the mirror.” The portrait tells the story of how Mbune transmitted HIV to her newborn daughter, who died from the virus, and how she is still dealing with her guilt and desire to have children. The artwork shows Mbune naked and covered in boils with her smiling daughter in her arms. “When I see this picture, where she is in my arms, it brings back those memories of being with her before she died.”

The Body Maps series is an incredibly important addition to the collection as it essentially voices and humanises one of the major current South African crises, HIV, through art and intricate, personal storytelling.

+27 11 381 3100

+27 11 381 3100